Short Film Reveals the Lunacy of Water Fluoridation

October 31, 2015 |

By Dr. Mercola

The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has hailed water fluoridation as one of the top 10 public health achievements of the 20th century.Beginning in 1945, it was claimed that adding fluoride to drinking water was a safe and effective way to improve people's dental health. Over the decades, many bought into this hook, line and sinker, despite all the evidence to the contrary.The featured film, "Our Daily Dose," reviews some of this evidence. As noted in the film's synopsis:"Filmmaker Jeremy Seifert lays out the dangers of water fluoridation informatively and creatively, highlighting the most current research and interviewing top-tier doctors, activists, and attorneys close to the issue.Through thoughtful examination of old beliefs and new science, the film alerts us to the health threat present in the water and beverages we rely on every day."

Share This Film With Those Still Sitting On the Fence on Fluoride!

The film may not offer many brand new revelations to those of you who are already well-informed about the history and documented hazards of fluoride.It was primarily created as an educational vehicle aimed at those who may not be aware of these issues, or who might not yet be entirely convinced that drinking fluoride isn't a good thing.So PLEASE, share this video with all of your friends and family who are on the fence on this issue, and ask them to watch it. It's only 20 minutes long, but it packs a lot of compelling details into those 20 minutes.Understanding how fluoride affects your body and brain is particularly important for parents with young children, and pregnant women.It's really crucial to know that you should NEVER mix infant formula with fluoridated tap water for example, as this may overexpose your child to 100 times the proposed "safe" level of fluoride exposure for infants!If your child suffers with ADD/ADHD, drinking fluoridated water may also worsen his or her condition. Ditto for those with underfunctioning thyroid. So please, do share this video with your social networks, as it could make a big difference in people's health.

Fluoride Is Both an Endocrine Disruptor and a Neurotoxin

Scientific investigations have revealed that fluoride is an endocrine disrupting chemical,1 and a developmental neurotoxin that impacts short-term and working memory, and lowers IQ in children.2It has been implicated as a contributing factor in the rising rates of both attention-deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD)3,4 and thyroid disease.Indeed, fluoride was used in Europe to reduce thyroid activity in hyperthyroid patients as late as the 1970s, and reduced thyroid function is associated with fluoride intakes as low as 0.05 to 0.1 mg fluoride per kilogram body weight per day (mg/kg/day).5

For over 50 Years, Fluoride Levels Were Too High, Government Admits

Children are particularly at risk for adverse effects of overexposure, and in April 2015, the US government admitted that the "optimal" level of fluoride recommended since 1962 had in fact been too high.As a result, over 40 percent of American teens show signs of fluoride overexposure6 — a condition known as dental fluorosis. In some areas, dental fluorosis rates are as high as 70 to 80 percent, with some children suffering from advanced forms.So, for the first time, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) lowered its recommended level of fluoride in drinking water7,8,9 by 40 percent, from an upper limit of 1.2 milligrams per liter (mg/L) to 0.7 mg/L.The HHS said it will evaluate dental fluorosis rates among children in 10 years to assess whether they were correct about this new level being protective against dental fluorosis.But just what is the acceptable level of harm in the name of cavity prevention?A number of studies10,11,12,13 have shown that children who with moderate to severe dental fluorosis score worse on tests measuring cognitive skills and IQ than peers without fluorosis — a clear revelation highlighted in the film, as some still insist that dental fluorosis is nothing more than a cosmetic issue.

The Price We Pay for Cavity Prevention

According to the film, the CDC estimates water fluoridation decreases dental decay by, at most, 25 percent. Recent research14,15 however, suggests the real effect may be far lower.Based on the findings of three papers assessing the effectiveness of fluoridation on tooth decay, the researchers concluded that water fluoridation does not reduce cavities to a statistically significant degree in permanent teeth.If that's the case, then why are we still jeopardizing our children's long-term thyroid and brain health by adding fluoride to drinking water?Fluoride — like many other poisons — was originally declared safe based on dosage, but we now know that timing of exposure can play a big role in its effects as well. Children who are fed infant formula mixed with fluoridated water receive very high doses, and may be affected for life as a result of this early exposure.Fluoride can also cross the placenta, causing developing fetuses to be exposed to fluoride. Considering the fact that fluoride has endocrine-disrupting activity, this is hardly a situation amenable to the good health of that child. It's important to realize that fluoride is not a nutrient. It's a drug, and it's the ONLY drug that is purposely added directly into drinking water.This route of delivery completely bypasses standard rules relating to informed consent, which is foundational for ethical medical practice. What's worse, there's no way to keep track of the dosage. And no one is keeping track of side effects.

Infants Are Severely and Routinely Overdosed on Fluoride

According to the recent Iowa Study, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the CDC, infants and young children are being massively overdosed on fluoride. This study, which is the largest US study conducted measuring the amount of fluoride children ingest, concluded that:

- 100 percent of infants receiving infant formula mixed with fluoridated tap water get more than the allegedly safe dose of fluoride. Some formula-fed infants receive 100 times the safe level on a daily basis

- 30 percent of 1-year-olds exceed the recommended safe dose

- 47 percent of 2- to 3-olds exceed the safe dose

Most Water Authorities Use Toxic Waste Product, Not Pharmaceutical Grade Fluoride

As stated, fluoride is a drug, and research into the health effects of fluoride is based on pharmaceutical grade fluoride.However, a majority of water authorities do not even use pharmaceutical grade fluoride; they use hydrofluosilicic acid, or hexafluorosilicic acid — toxic waste products of the phosphate fertilizer industry, which are frequently contaminated with heavy metals such as arsenic, mercury, cadmium, lead, and other toxins.This is a key point that many fluoride proponents fail to address when arguing for its use. Indeed, holding elected officials accountable for procuring proof that the specific fluoridation chemical used actually fulfills fluoride's health and safety claims and complies with all regulations, laws, and risk assessments required for safe drinking water, has been a successful strategy for halting water fluoridation in a number of areas around the US.While the idea of hiding toxic industrial waste in drinking water would sound like a questionable idea at best to most people, it was welcomed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In a 1983 letter, Rebecca Hanmer, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Water, wrote:"... In regard to the use of fluosilicic acid as a source of fluoride for fluoridation, this Agency regards such use as an ideal environmental solution to a long-standing problem. By recovering by-product fluosilicic acid from fertilizer manufacturing, water and air pollution are minimized, and water utilities have a low-cost source of fluoride available to them..."

Data and Science Does Not Support Water Fluoridation

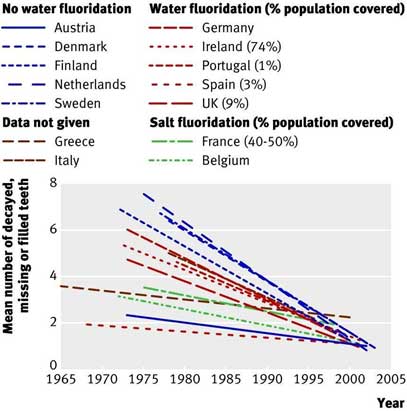

Ninety-seven percent of Western European countries do not fluoridate their water, and data collected by the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that non-fluoridating countries have seen the exact same reduction in dental cavities as the US,16where a majority of water is still fluoridated. If fluoride were in fact the cause of this decline, non-fluoridating countries should not show the same trend.Clearly, declining rates of dental decay are not in and of themselves proof that water fluoridation actually works. It's also worth noting that well over 99 percent of the fluoride added to drinking water never even touches a tooth; it simply runs down the drain, contaminating and polluting the environment.Source: KK Cheng et.al. BMJ 2007.17 Rates of cavities have declined by similar amounts in countries with and without fluoridation.

Ending Fluoridation Will Be the Greatest Public Health Achievement of the 21st Century

Despite the fact that the scientific evidence does not support fluoridation, those who question or openly oppose it are typically demonized and written off as crazy conspiracy theorists. Many fluoride supporters claim the science of fluoridation was "settled" some 50 years ago — effectively dismissing all the revelations produced by modern science! To defend their position, they rely on outdated science, because that's all they have. You'd be extremely hard-pressed to find modern research supporting water fluoridation.Indeed, as noted in the film, ending water fluoridation will be one of the greatest public health achievements of the 21st Century, and I for one will not stop until that happens. To learn more about why water fluoridation runs counter to good science, common sense, and the public good, please see the following video, which recounts 10 important fluoride facts.

The Best Cavity Prevention Is Your Diet

The best way to prevent cavities is not through fluoride, but by addressing your diet. One of the keys to oral health is eating atraditional diet or real foods, rich in fresh, unprocessed vegetables, nuts, and grass-fed meats. By avoiding sugars and processed foods, you prevent the proliferation of the bacteria that cause decay in the first place.According to Dr. Francesco Branca, Director of WHO's Department of Nutrition for Health and Development:18 "We have solid evidence that keeping intake of free sugars to less than 10 percent of total energy intake reduces the risk of overweight, obesity and tooth decay."Other natural strategies that can significantly improve your dental health is eating plenty of fermented vegetables, and doing oil pulling with coconut oil. Also make sure you're getting plenty of high quality animal-based omega-3 fats, as research suggests even moderate amounts of omega-3 fats may help ward off gum disease. My favorite source is krill oil